I’m fascinated by beauty. It is my final fortification against materialism, a barrier from reducing the world to numbers. Sam Harris’s arguments are very sound—they explain things, fill in the gaps. But atheism specializes in the details and misses the sunsets and the waterfalls and Beethoven’s Ninth and Charles Dickens.

The sky’s on fire in the west tonight

A chorus of pink, purple, blazing orange

The air pulses with meaning and—

I think of random particles,

of chance and infinite typewriters,

but no cold device could make the beauty,

nor make me understand it.

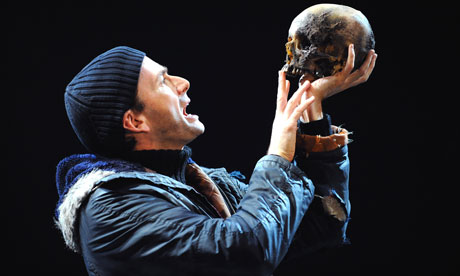

It’s my take-down of the infinite monkey theorem—the idea that that if you give a monkey infinite time and a typewriter, he’ll eventually type Shakespeare’s plays, just by balance of probability—all of which is a metaphor for the random perfection of the universe.

There’s a problem with this (besides the fact that we know the universe hasn’t been around for infinity.)

Sure, you’ll eventually get the script for Hamlet—but that doesn’t account for monkeys understanding Hamlet, much less Hamlet’s existential musings. C.S. Lewis wrote that “reason is the natural organ of truth; but imagination is the organ of meaning. Imagination, producing new metaphors or revivifying old, is not the cause of truth, but its condition.”

Sure, you’ll eventually get the script for Hamlet—but that doesn’t account for monkeys understanding Hamlet, much less Hamlet’s existential musings. C.S. Lewis wrote that “reason is the natural organ of truth; but imagination is the organ of meaning. Imagination, producing new metaphors or revivifying old, is not the cause of truth, but its condition.”

Of course, we can say that meaning is something we make up, which is fair enough, but we’re kind of cutting the ground from under our feet. We have no more evidence to trust reason than we do to trust meaning besides the fact that both seem to make sense. We can doubt one or the other, but it’s usually at the expense of both.

It’s one thing to talk about a star as “a massive, luminous sphere of plasma held together by its own gravity,” and quite another to write the line “Silence was pleased: now glowed the firmament with living sapphires.”

It wouldn’t stand up in a court of law, but maybe that’s all right. Our culture is saturated with Enlightenment logic—i.e. only what I can prove empirically is true. Amusingly, we don’t really live like we believe that—very few of us fulfill our beliefs in our actions anyway, but no one in our culture lives as if feelings don’t matter. In fact, we give them an inordinate amount of importance. Have you seen Titanic? Talk about a celebration of feelings. Terry Mattingly wrote:

For millions, the Titanic is now a triumphant story of how one upper-crust girl found salvation -- body and soul -- through sweaty sex, modern art, self-esteem lingo and social rebellion. ‘Titanic’ is a passion play celebrating the moral values of the 1960s as sacraments.

Don't even get me started on Twilight.

Yet we place no value on emotion intellectually—we indulge endlessly in escapist, passionate romantic blockbusters, yet admit no entry for these desires into the sterile intellectual world we call “value.” C.S. Lewis, young atheist, felt this keenly when he wrote that he cared “for almost nothing but the gods and heroes, the garden of the Hesperides, Launcelot and the Grail, and [believed] in nothing but atoms and evolution and military service.” He would later highlight this intellectual schizophrenia in his excellent book The Abolition of Man. We have compartmentalized debates to such an extent that love is a mere chemistry experiment. It’s indicative in our casual approach to sex that we place more importance on physical rather than spiritual connections.

Christianity bridges the gap. While answering a number of important issues intellectually (origin of the universe, historical person of Jesus,) it also encompasses metaphysical questions stemming from the heart, and concerning beauty, desire, and sin.

The story of Christ has all the charm, emotional appeal, and internal consistency of a good fairytale (something we, in all our modern urbanity, still celebrate), and yet can be proved to have existed in the material universe. I can just see the Jerusalem Post—Man Claims to Be God. Massive Battle Between Good and Evil. Outlaw Promises Spiritual Rewards to Followers. The Dead Walk Among Us. Prophecy Fulfilled. Return of the King. And next thing you know, Christianity is the number one religion on the planet. It’s so crazy—so clichéd, in a way, it had to happen. Credo quia absurdum.

The story of Christ has all the charm, emotional appeal, and internal consistency of a good fairytale (something we, in all our modern urbanity, still celebrate), and yet can be proved to have existed in the material universe. I can just see the Jerusalem Post—Man Claims to Be God. Massive Battle Between Good and Evil. Outlaw Promises Spiritual Rewards to Followers. The Dead Walk Among Us. Prophecy Fulfilled. Return of the King. And next thing you know, Christianity is the number one religion on the planet. It’s so crazy—so clichéd, in a way, it had to happen. Credo quia absurdum.

In the Incarnation (as I’ve written before), sacred and the secular fuse into one. God, a spirit if there ever was one, takes on a decidedly less real state of being, flesh and blood. Jesus famously refused to keep his commands in the abstract, “Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to me.” “Faith without works is dead.” While his faith was made up of spiritual truths, it finds its roots in dirty, gritty, bloody reality.

He was too metaphysical for the empiricist Sadducees, and too literal for the fundamentalist Pharisees. In a world operated by Harvard-groomed Sadducees, it’s refreshing to be vindicated in my love of beauty and meaning, to be reminded that there is a purpose underlying things. At the same time, Christianity gives material evidence for its truth (though not relying fully on it, as scientism). This double satisfaction is the only way to really live healthfully.

Take this gorgeous segment of writing in A Passage to India:

She had come to that state where the horror of the universe and its smallness are both visible at the same time—the twilight of the double vision in which so many elderly people are involved. If this world is not to our taste, well, at all events there is Heaven, Hell, Annihilation—one or other of those large things, that huge scenic background of stars, fires, blue or black air. All heroic endeavour, and all that is known as art, assumes that there is such a background, just as all practical endeavour, when the world is to our taste, assumes that the world is all. But in the twilight of the double vision, a spiritual muddledom is set up for which no high-sounding words can be found; we can neither act nor refrain from action, we can neither ignore nor respect Infinity.

In the “twilight of the double vision,” we are left immobile, terrified by our insignificance in the face of the pinched smallness of the world, while trying to escape it into “Heaven, Hell, Annihilation—one or other of those large things.” (Parenthetically, this is the entire plot of Hamlet: “To be or not to be?”) The only solution must be a paradox, an idea of at once embracing both the world and the heavens. My philosophy in a nutshell (I know I quote this all the time, but still):

Our attitude towards life can be better expressed in terms of a kind of military loyalty than in terms of criticism and approval. My acceptance of the universe is not optimism, it is more like patriotism. It is a matter of primary loyalty. The world is not a lodging-house at Brighton, which we are to leave because it is miserable. It is the fortress of our family, with the flag flying on the turret, and the more miserable it is the less we should leave it. The point is not that this world is too sad to love or too glad not to love; the point is that when you do love a thing, its gladness is a reason for loving it, and its sadness a reason for loving it more.

~G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy

This segues into the Christian idea of death. If the world is all there is, we must cling to it with every fiber of our being, nails clawing at the ragged fragments of an empty life. If the world is unimportant, an illusion, there is no reason not to blow our brains out—abandon ship, as it were. Instead, patriotism means that we must die fighting, but with heads held high. Fall clutching the Flag of the World, and know that it’s just a flag, and not a very decent one at that—but ours.

Very few modern Christian stories capture this (good fantasy is a bright spot—even Harry Potter does a decent job). We take on the role of deserters, speaking of heavenly rewards and golden streets and abandoning the sadness of this world. Unbelievers rightly despise this escapist attitude. Yet their view that the world is all there is is just as useless, offering no motivation for philanthropy or “heroic endeavour.” They’re caught in Hamlet’s double-mindedness, producing fatalism or the garish sentimentality of Titanic. And of course, neither of these ideas are Christianity. We have a job to do.

“Authority is not given to you, Steward of Gondor, to order the hour of your death,” answered Gandalf. “And only the heathen kings, under the domination of the Dark Power, did thus, slaying themselves in pride and despair, murdering their kin to ease their own death . . . Come! We are needed. There is much that you can do.”

~Return of the King

Longish

.png)

This was really good, Hannah. I enjoyed the read. Again astonished at your wisdom. Good thing I bought Shakespeare collection book, because yet again, I tell myself I need to truly "find out" what Hamlet really is as a story. I'm aware of Titanic, and know enough about it to agree with your associating it with unfounded sentimentalism--nothing truly real. It's a story that again, grasps at thread of truth, not a tapestry. Will be sharing this!

ReplyDeleteHamlet's my favorite Shakespeare play. My favorite version is probably David Tennant's, though Branagh is pretty brilliant, and Paul Scofield is my favorite version of Hamlet's dad (Mel Gibson's, in that case.)

ReplyDelete