“Stephen Fry and

Hugh Laurie shouldn’t age,” says my Dad, leaning against the kitchen counter.

“Seeing them get old…it just doesn’t…it’s weird.”

Back in the ’90s,

the two British actors co-starred in Jeeves

and Wooster. Fry and Laurie played, respectively, the unflappable,

omniscient valet, Jeeves, and his dimwitted, talkative employer, Bertrum

Wilberforce Wooster. The stories are set in an idyllic pre-war atmosphere,

where the greatest ill that can befall a man is ridiculous romantic dilemmas or

bogus get-rich-quick schemes. Let’s be honest, it’s pure escapism—albeit

escapism with lively wit, brilliant plotting, and hilarious (if somewhat

one-dimensional) characters. No one ages and, of course, no one dies.

That’s why it’s

so weird to see old Fry and Laurie. I had a similar reaction to seeing Anthony

Valentine in a modern movie. I’d had a crush on him in the 1975 TV show Raffles…and suddenly, he was in his

seventies. He's old enough to be my grandfather.

Why this violent

reaction, this jerking back from reality?

C.S. Lewis writes

in Reflections on the Psalms:

We are so little reconciled to time that we are

even astonished at it. “How he’s grown!” we exclaim, “How time flies!” as though

the universal form of our experience were again and again a novelty. It is as

strange as if a fish were repeatedly surprised at the wetness of water. And

that would be strange indeed; unless of course the fish were destined to

become, one day, a land animal.

Wikipedia tries

to quantify it: Death is the permanent

cessation of all biological functions that sustain a particular living

organism.

Aging and death

are things that seldom intrude into escapist fiction, but often into modern

novels. Reading lists are packed with stories written by intrepid, Ivy-league

graduates willing to take an unflinching look at the gritty world and describe

the random, ugly squalor of death and life. There is no room for happiness in

this Quentin Tarantino outlook.

This is true

intellectual bravery, we are told.

A brief

side-track.

J.R.R. Tolkien

was constantly accused of writing escapist books. He fiercely denied the charge:

“Fantasy is

escapist, and that is its glory. If a soldier is imprisoned by the enemy, don't

we consider it his duty to escape?. . .If we value the freedom of mind and

soul, if we're partisans of liberty, then it's our plain duty to escape, and to

take as many people with us as we can!”

Thus his purpose

was to effect an escape from materialism—from the idea that we are at home

here. We are destined to become land animals.

Secondly, he

turned the criticism back at the critics, pointing out that modern culture in

general is obsessed with escaping the one reality which cannot be escaped: death.

By contrast, his books, and many fairytales, take death by the horns and defeat

it properly. Tolkien, speaking about fantasy writers, replies via his poem Mythopoeia:

It is not they that have forgot the Night,

or bid us

flee to organized delight,

in

lotus-isles of economic bliss

forswearing

souls to gain a Circe-kiss

(and

counterfeit at that, machine-produced,

bogus

seduction of the twice-seduced).

Such isles

they saw afar, and ones more fair,

and those

that hear them yet may yet beware.

I return to the

subject. All you have to do is look at society to see we will do anything

humanly possible to escape death. Like a condemned prisoner in A Tale of Two Cities, our “hold on life

is strong, and…very, very hard, to loosen; by gradual efforts and degrees

unclosed a little here, it clenched the tighter there.”

That’s not to say

it’s true over the board. Many, rather than avoiding it, give in to it. These

are the aforementioned Ivy League Tarantino worshippers. The result is despair.

Tolkien: “Before

them gapes/ the dark abyss to which their progress tends.”

N.D. Wilson: “Does

God tell stories of heroin addicts and alleys in Seattle? Yes, he does. And so

you have the edgy hipster types who say ‘That’ll be the only story I tell.’ I

will spend all my time in the alleys of Seattle, and I will not acknowledge the

presence of anything cute. Sunsets…kinda tacky. I will always have the sun

setting over an industrial wasteland. I will never have that pink fluffy

cumulus effect…because that’s just weak.”

You have the right-to-die

movement, who try to gloss over the despair with a stern-faced, so-called

bravery, but this too, is really the desire to run. They want to escape too. They

want to escape suffering or a “loss of dignity”, which are apparently fates worse

than death. They are afraid of pain and humility, two elements which God has

used countless times to refine his protagonists.

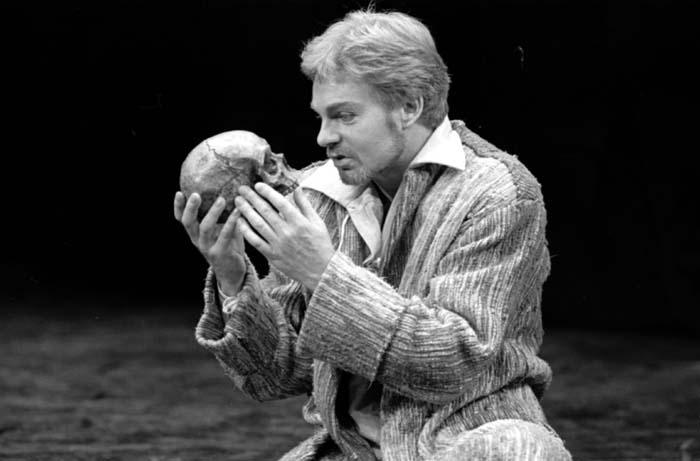

To be, or not to

be: that is the question:

Whether 'tis

nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and

arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms

against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing

end them? To die: to sleep;

No more; and by a sleep to say we end

The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to, 'tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wish'd.

Continued in Part 2

Longish

No comments:

Post a Comment

WARNING: Blogger sometimes eats comments - copy before you post.